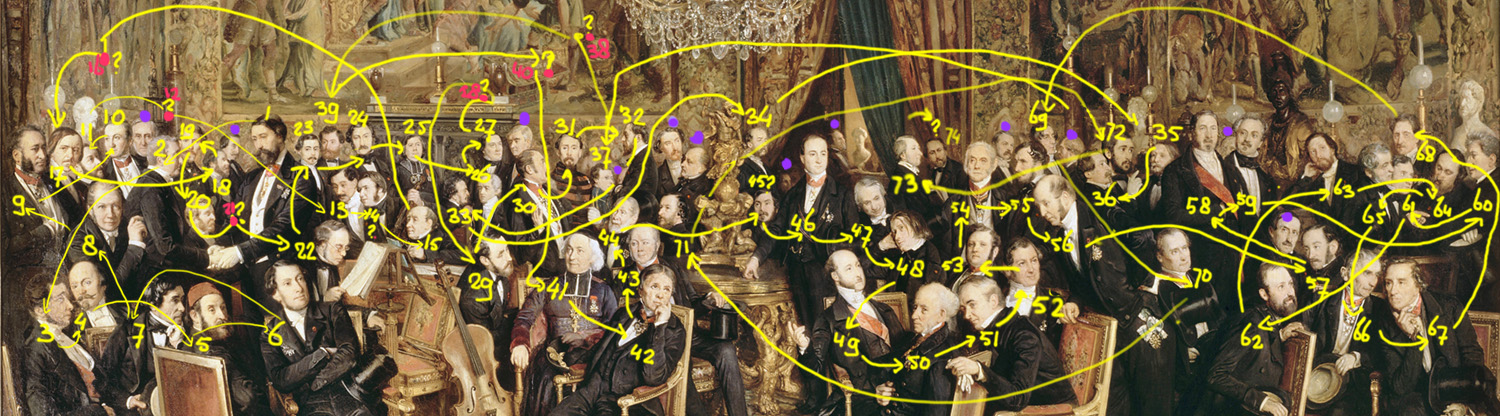

These regional newspapers, digitized in April 2024 —nine years after my initial research— offer a significantly longer list of individuals in Une Soirée au Louvre than any account published in the Parisian press.

Both articles appear to rely on a single source and contain multiple orthographic inaccuracies, raising questions about their reliability. The frequency and nature of the errors suggest that the list may have been hastily transcribed as names were dictated, and possibly misinterpreted at a later stage. The texts are reproduced “as is,” without editorial comment or critical apparatus. The images and full articles are accessible via the hyperlinks above.

Several noteworthy observations:

- The articles claim the painting was completed in March 1855. Since the official debut occurred during the May Salon, the author must have had privileged early access.

- Both articles assert the presence of seventy-five individuals but list only seventy-four.

- The Courrier included general Bougenel78. The Gazette omits his name.

- The Gazette includes fifteen misspelled names. The Courrier corrects several, listing only eight incorrect entries. In one instance, it merges Jaubert [Jobert] and Lamballe01 into a single name, while maintaining the mistaken total of seventy-five.

- Given that no engraving of Soirée au Louvre existed at the time (the first and only, by Dayot, was completed in 1900), the journalist would not have known the precise content or number of faces depicted.

- The author was evidently unfamiliar with several individuals —most notably, de Nieuwerkerke’s uncle and father, whose presence is omitted. The entry “Charles Giraud,” for example, gives no indication of whether it refers to the Minister66 of Public Instruction or to Eugène Giraud’s brother47.

- Only one violinist is mentioned, although the painting clearly depicts two.

- Some individuals included in the articles lack the requisite Légion d’Honneur rank to correspond with their painted counterparts.

- A musician named “Haumann” is cited, yet the prefect of the Seine, Baron Haussmann07 —whose high honors and later inclusion in Dayot’s engraving confirm his importance— is conspicuously absent.

- The descriptive sequence of individuals is disorganized: although it begins logically with de Nieuwerkerke and Visconti, it proceeds erratically, making it difficult to follow.

- No addenda or corrections appear to have followed these publications after the painting’s exhibition.

Roughly a dozen names differ from the findings I established in 2015. However, these articles overlook —or misidentify— several individuals confirmed by prior scholarship, including architect Viollet-le-Duc40a (the subject of a 2015 Beaux-Arts issue) and historian Ernest Renan27a.

Given the core group of celebrated restoration architects —including Viollet-le-Duc, Duban, Duret, Lassus, and inspector Mérimée— who were openly supported by the Emperor and known to have attended de Nieuwerkerke’s vendredi-soirées, it is implausible to suggest that Viollet-le-Duc would have been excluded.

His supposed substitute, the animal painter Troyon40b, was famously reclusive and avoided Parisian society; there is no record of his participation in these salons.

Taken together —the omissions of key figures, the numerous misspellings, and inconsistent structure— it is plausible that the articles were based on verbal dictation.

The selection of individuals for Une Soirée au Louvre was overseen with care by de Nieuwerkerke, who also applied the same selective process to the caricatures of Eugène Giraud.

Such rigorous preselection would not have been tolerated by other artists like Ingres39 or Heim28b, who likely would have resisted such curatorial oversight. Biard did not have that seniority.

De Nieuwerkerke16, Horace de Viel-Castel43, Eugène Giraud11, or Count de Morny48 would have been capable of accurately identifying all participants, including de Nieuwerkerke’s family members.

Painter Biard himself likely lacked that knowledge. He never attended the soirées and sketched whomever de Nieuwerkerke sent to his cramped studio high above Place Vendôme. It is entirely possible that he rendered more sitters than ultimately appeared in the final (revised) composition.

What is perhaps most surprising is that these regional newspapers attempt to enumerate attendees when none of the major Parisian publications —many of which covered the soirées regularly, including Le Ménestrel— produced anything more than brief mentions, typically citing two dozen names out of the total of eighty. A Parisian paper with equivalent claims would carry far greater credibility, particularly as its writers were familiar with proper spellings for figures such as the well-known Russian ambassador Kisseleff, frequently mentioned in their columns.

It is conceivable that the original contributor to these regional reports visited Biard’s studio and compiled a list of names based on observations or studio sketches —not necessarily individuals who appeared in the painting. The writer clearly had little contextual knowledge of who the subjects were or where they were placed, perhaps except for a few museum officials.

Analysis of the unconfirmed names in the press articles

Despite the ambiguities present in both articles, most names correspond closely with those identified in my 2015 analysis. In cases of uncertainty, I have deliberately presented alternative identifications, allowing the reader to assess the available options and actively engage with the process.

It is to be hoped that new press sources —ideally from Paris— will come to light and help clarify the accuracy of the names listed in these two provincial publications.

At present, eight names cannot be verified by any existing data or are in significant conflict with information associated with other candidates. These are:

- Théodore Haumann, Belgian violinist 1808–1878)

There is no facial match. Given the omission of Seine Prefect Georges Haussmann from these articles, the most plausible explanation is that the name was misheard or misrecorded.

Haumann held no Legion of Honour title in 1855. The decoration visible in the image may have been a Belgian distinction.

- Louis Gueymard, tenor (1822–1880)

While he did attend a vendredi-soirée, there is no facial correspondence with any unidentified figure —only with already confirmed individuals such as painter Muller18 or Barbet de Jouy44b. He held no Legion of Honour rank.

- Léonard Hermann (known as Hermann-Léon), baritone (1814–1858)

He sang at one of the vendredi-soirées in March 1851, probably before the painting was commissioned. Apart from a caricature in performance costume, no reliable image survives. He had no Legion of Honour distinction.

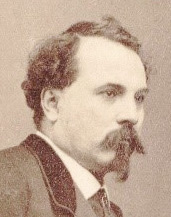

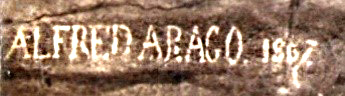

- Alfred Arago, painter and Beaux-Arts inspector/conservator (1815–1892)

Few images exist, though available likenesses resemble the figure in question. Long overshadowed by his father, physicist François Arago, he collaborated from the late 1850s with others in the painting, such as Baroche and Reiset.

Rumors suggest he aspired to replace de Nieuwerkerke, making his inclusion unlikely.

One of the few enduring legacies of this “conservator” is the graffiti he carved into the façade of the Abu Simbel temple in Egypt in 1867.

- Charles Rogier, Belgian statesman and minister (1800–1885)

There is no documentation of his attendance at any vendredi-soirée. One record does place him and his wife at a dinner hosted by Minister Fould in 1856. His distinctive hairstyle would have made him easy to identify. The accompanying 1855 sketch provides a reliable likeness from the period. Rogier held the Grand Officer rank in the Legion of Honour since 1841, which should have been reflected with the appropriate sash and cross. The only unconfirmed figure in the relevant area of the painting is engraver Texier30, yet there is no visual match, and Texier displays the red boutonnière of the Chevalier rank, not the insignia of a Grand Officer —unless Biard represented him with uncharacteristic inaccuracy.

- Elzidor Naigeon, painter and deputy conservator at the Luxembourg Museum (1797–1867)

No reliable portraits are available —only one image that may depict a relative. Naigeon is unmentioned by Viel-Castel, and as a deputy, he may not have had the seniority to participate alongside higher-ranking conservators. There is no documented connection with de Nieuwerkerke, and his name never appears in Le Ménestrel. - Alexis Dupont21b, opera singer (1796–1874)

I have included Dupont as an alternative to tenor Duprez21a, as both share striking facial similarities. However, Dupont's 1856 conviction for sexual abuse of minors —acts allegedly dating back to the late 1840s— would likely have been known within elite circles and makes his selection over the more celebrated and uncontroversial Duprez implausible.

Beyond the lack of facial correspondence, it would have been highly inappropriate for Biard —a commissioned artist who never attended the soirées— to place himself in a prominent position among aristocratic guests.

Such a move would have required explicit approval from de Nieuwerkerke. Following long-established artistic tradition, the more plausible location for a discreet self-insertion would be figure36.

Taking into account both the negative reception the painting received at the 1855 Salon and the evidence of a partial revision to remove the actress Rachel81 in 1854, it is reasonable to infer that de Nieuwerkerke viewed the painting as a disappointment. Though it remained in his Louvre apartment for fifteen years, he appears never to have disclosed any details to the press or intermediaries with media access.

The first known reproduction of the painting was made in 1900 by Dayot, who catalogued imperial artworks housed at the Empress’s residence in Farnborough, England.

Should new information emerge that supports the accuracy of these provincial articles, I will add it here.