Émilien de Nieuwerkerke (1811–1892), Count, Sculptor, Director General of Museums

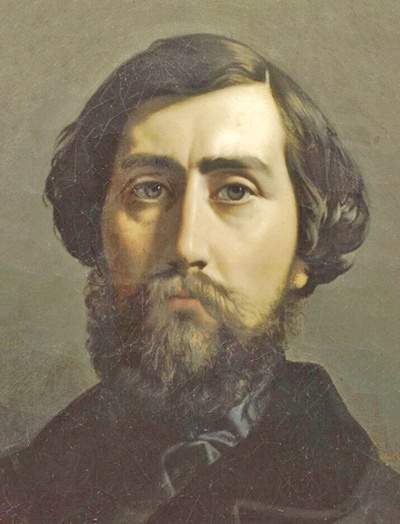

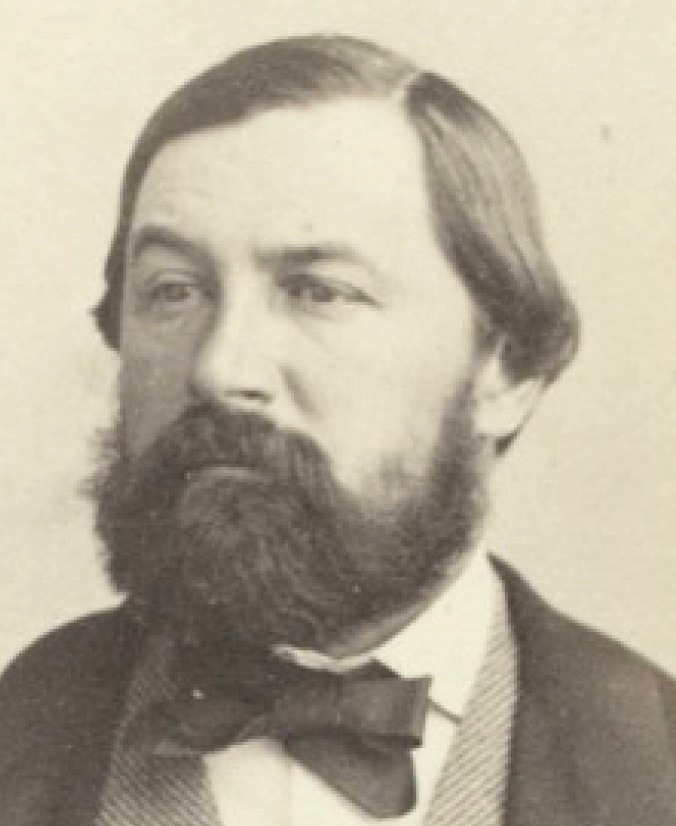

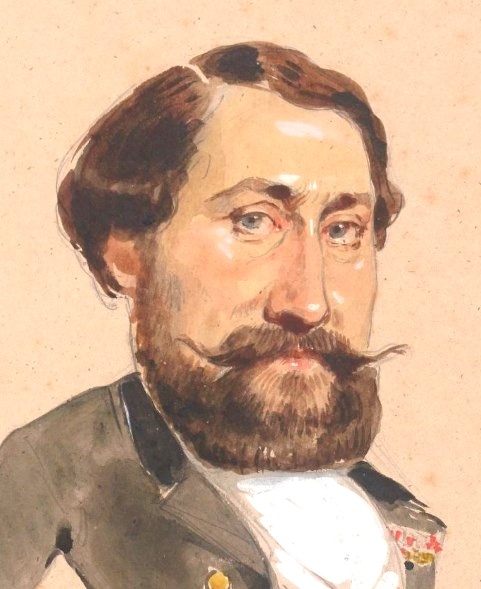

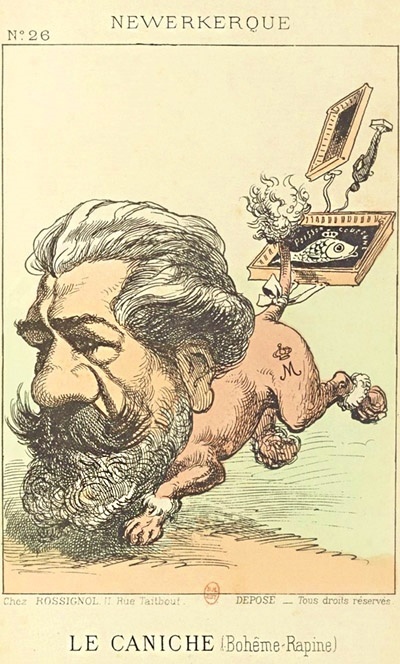

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: by Lehmann (1846); 3rd: early photo by Richelieu (c.1850); 4th: drawing by Ingres (1856); 5th:caricature by Giraud drawn early 1850's at de Nieuwerkerke's soirée.

At the most prominent place in the painting stands Émilien de Nieuwerkerke —ambitious, intelligent, and strikingly handsome, known among his contemporaries as “le beau Batave.” He is shown welcoming Visconti09 at one of his vendredi-soirées, emblematic of his influential role in Parisian artistic circles.

Born in Paris into a family with Dutch heritage, Émilien’s lineage traced back to his grandfather, Willem van Nieuwkerk, an illegitimate son of William IV of Orange. His father, Charles71, secured his place in French aristocracy through marriage to Louise-Albertine, daughter of the Marquis de Vassan, granddaughter of the Duke of Orléans, and cousin to Viel-Castel43. Émilien was born five months after their wedding.

During a cultural trip to Italy in the 1830s, he resolved to become a sculptor, training under Baron Marochetti. Though he never reached the technical mastery of artists like Pradier03 (one of his teachers), critics recognized his considerable talent. Among his most esteemed works was the equestrian statue of Dutch founding father William the Silent of Orange, erected in The Hague.

While traveling through Italy in 1845, he fell in love with Princess Mathilde Bonaparte—intellectual cousin to future Emperor Louis-Napoléon. Mathilde, separating from her husband Prince Demidoff in 1846, returned to Paris with Émilien, who had been married since 1832 to Thécla de Montessuy. The two lived together as husband and wife until their separation in August 1869.

Louis-Napoléon recognized Nieuwerkerke’s leadership abilities, appointing him in December 1849 as Surintendant des Beaux-Arts at the Louvre. Following the coup of 1851, he entrusted Émilien with overseeing fine arts in the imperial household—effectively granting him control over all Parisian museums and imperial art collections.

Understanding the power of reputation and relationships, Émilien actively cultivated a network among conservators, artists, and Parisian elites, recognizing that his role depended on strong ties to the art world. To reinforce these connections, he established weekly vendredi-soirées in April 1850 at his Louvre apartment.

Amid opulence, his exclusively male guests engaged in musical performances, lectures, and after-party discussions on politics and culture. Thanks to de Nieuwerkerke’s artistic and social endeavors, his soirées became so influential that Napoleon III famously remarked: “The royal court isn’t at the Tuileries— it is at the Louvre.”

Seeking to memorialize these gatherings, he appointed Princess Mathilde’s art instructor, Eugène Giraud11, as resident caricaturist. He also commissioned François Biard36 to produce a grand painting in the spirit of Heim28’s famous Distribution des Récompenses, ensuring his soirées would be immortalized with portraits of elite attendees.

However, when Soirée au Louvre was finally unveiled at the 1855 Salon—following a year-long delay due to a redesign of the composition—critics dismissed it as “mediocre”—valued more for its subjects than its artistic execution. Nieuwerkerke’s silence regarding the painting’s reception suggests it failed to meet his expectations.

Following his dismissal from his position after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, he fled to England, selling his vast art collection to his friend Sir Richard Wallace, son of the 4th Marquess of Hertford. Today, the Wallace Collection is one of the largest private art collections in the world.

By 1872, Émilien retired to Villa Gattaiola near Lucca, Italy, where he lived alongside two princesses from the Cantacuzène family of Odessa—Maria and her daughter Olga, whom he had known through Mathilde’s literary salon since the early 1860s. Rumors suggest they were successively his lovers, with his muse Olga ultimately inheriting his estate near Lucca.

Until 1929, the painting remained in Farnborough, England, the exile residency of the Imperial family. In 1900, art historian and inspector Armand Dayot commissioned an engraving of it for his book Le Second Empire.

It now forms part of the permanent collection of the Imperial museum at the Château of Compiègne.

Note: Nieuwerkerke is depicted wearing a red collar, though he officially received the Commandeur rank of the Légion d’Honneur only on December 30, 1855. The decoration may instead have been an Ottoman Médjidié order, awarded to him in 1852. His hairstyle also underwent a notable shift—up until the early 1850s, he parted his hair on the right (as seen in images 2 and 3), whereas later portraits consistently show a left-side parting.