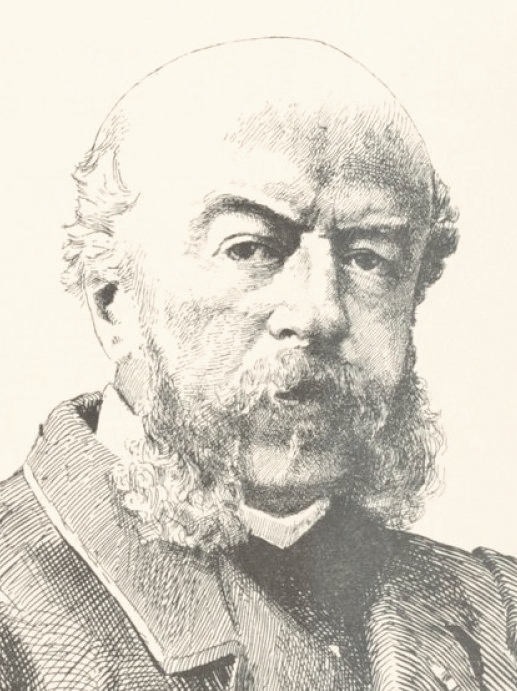

Count Horace Salviac de Viel-Castel (1802 -1864), historian, conservator of the Louvre

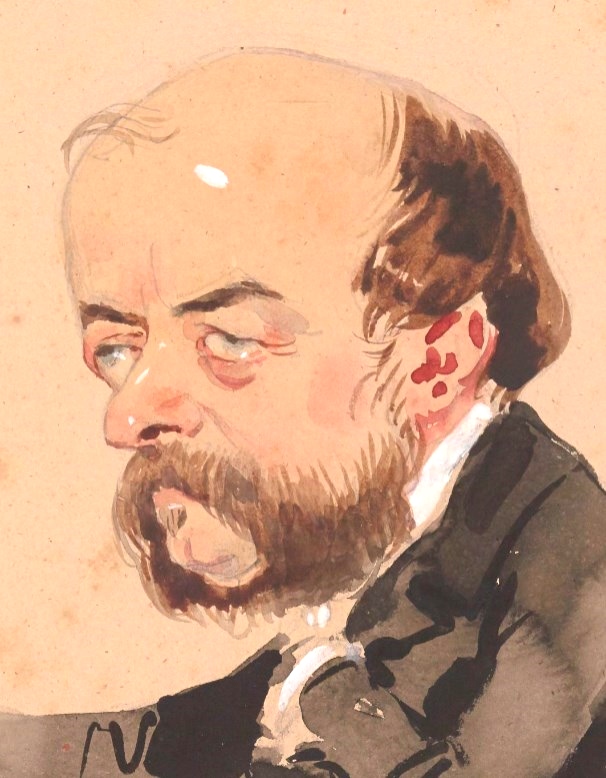

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: engraving by Dennoulin (mid 1850s); 3rd: Receuil. Actualités Politiques (1856); 4th: caricature by Eugène Giraud drawn late 1850's at Nieuwerkerke's salon (and Viel's atelier).

Partially hidden behind the large table with a statue of Jupiter statue striking down the Titans, stands Count Marc-Roch-Horace de Viel-Castel, the spider in the web in the vendredi-soirées and the organization of the Louvre. A collector, not of art, but of social data. Times haven’t changed…

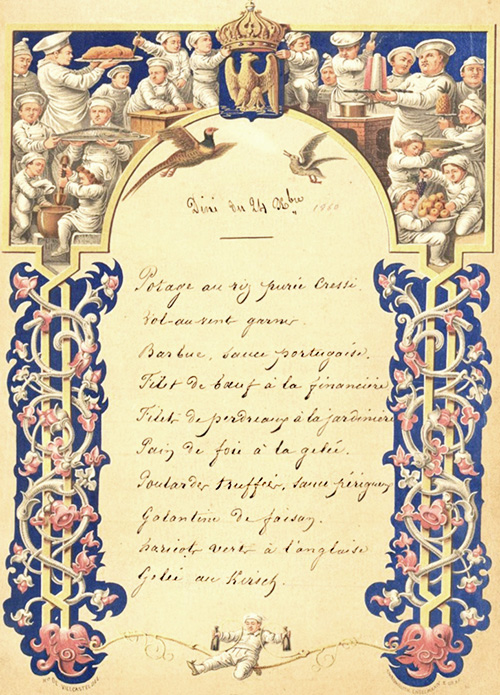

Where Eugène Giraud11 sketched watercolor caricatures of the guests, it was Horace de Viel-Castel who knew everything about everyone, and recorded all these observations in his diaries. Between Jan. 29, 1851 and Aug. 27, 1864, he fills over 2,000 pages.

Viel-Castel's family was close to the Bonapartes. He knew Louis-Napoleon since childhood and was a remote cousin of de Nieuwerkerke’s mother. Because of his birth, and intellect, he could have reached highest levels in government, but his lack of ambitions landed him in 1851 at the position of secretary of the general direction of the Louvre.

He preferred the presence of artists, such as his friend, the poet Alfred de Musset73, and was very close to his brother Victor45. He was devoted to emperor Napoleon III, and considered anyone opposing the emperor an enemy. Near to his heart was Princess Mathilde, with whom he dined over one hundred times. His expertise in arts was recognized, and he was admired and decorated for his competence as judge in the Beaux-Arts competitions.

Protégé of de Nieuwerkerke16, with an atelier at the Louvre, Viel-Castel attended nearly all the vendredi-soirées, and chaired them in de Nieuwerkerke’s absence.

At these soirées and intimate after-parties at his atelier, smoking and sipping tea, he became privy to many personal secrets, which he wrote down in ‘livres noirs’ (black booklets). These Mémoires (published in 1883) range from humoristic to sarcastic and salacious, yet maintaining an intellectual level. In that respect, his diary greatly surpasses the Journal of the brothers Goncourt, which is primarily scandalous.

Viel-Castel’s diaries give us a first-row view of the characters, social interactions, and intimate affairs of the persons in Une Soirée au Louvre.

Together with de Nieuwerkerke he may have been the only one who knew all the persons in the painting, including their affairs and mistresses. If only he would have spent half an hour in 1855 to write these names down…

Viel-Castel became ill late 1862. His declining health (caused by a stomach disease) was reflected in increasing negativity in his observations.

On March 11, 1863, in the new journal La France, he criticised de Nieuwerkerke's traditional art selection process for the annual expositions and suggested improvements. Although others found his article rather moderate, with "less the character of a criticism than of observations respectfully submitted to the competent minister, " de Nieuwerkerke fired him the next day and appointed Barbet de Jouy44a in his place as conservator of the Museum of Sovereigns.

The Parisian press wrote: "Mr. de Viel-Castel's greatest pleasure is to bite the hand he has just licked."

Viel-Castel’s recommendation, however, together with the artist protests, led the emperor to initiate the now famous Salon des Refusés in 1863. In November that year, joint activities (reinforced by the emperor) by de Nieuwerkerke, Mérimée54, and Viollet-le-Duc40a resulted in a reorganization of the traditional structure of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Exiled from the happy life of soirées and dinners with princess Mathilde, Viel-Castel focused on writing publications about the political future of the French Republic. Many of them are spot-on predictions, confirmed by history. His last diary note was written five weeks before his death.

Under his caricature, Giraud has written: “Voilà pourquoi je suis comme sa” (That's why I'm like this).