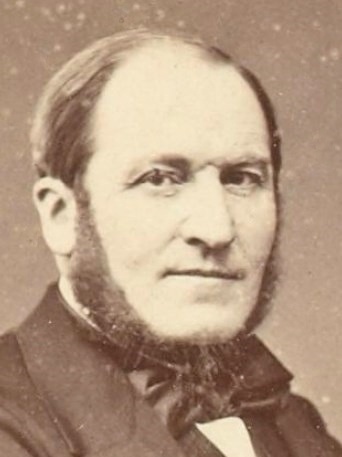

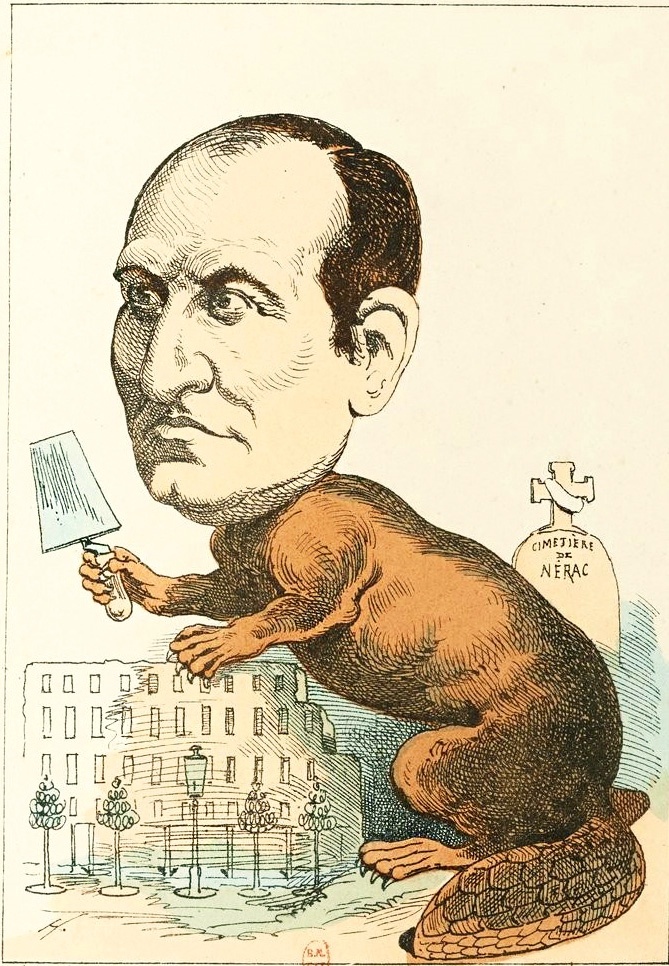

Georges Eugène Haussmann, baron (1809-1891), Prefect of the Seine

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: gravure Robert (early 1850s); 3rd: engraving (late 1850s); 4th: Adolpe Yvon (c.1853); 5th: photo by Petit (1865).

Georges Haussman is a figure known to all—the boulevard bearing his name remains one of Paris’ vital arteries. Though originally trained in law, his ambition led him to a career in public administration. In June 1853, Napoleon III appointed him as Prefect of the Seine department, tasking him with accelerating the sluggish urban renewal plans that the emperor envisioned. His presence at vendredi-soirées allowed members of the aristocracy to remain informed about the transformation of Paris.

While Haussmann was not an architect, he excelled in navigating the complex and often manipulative political landscape necessary to implement his grand reconstruction projects. A major milestone was the completion of several key boulevards in time for the 1855 Exposition. His bold urban planning provoked significant opposition—not only from civilians but also from Empress Eugénie, who was displeased to find the driveway of the Luxembourg Palace significantly reduced to accommodate one of Haussmann’s new boulevards, Saint-Germain. Many aristocrats and officials expressed similar frustrations over the transformation of historical spaces, viewing the modernization as disruptive to the city’s heritage.

Although unpopular at the time, Napoleon III’s urban overhaul was essential in modernizing a medieval city plagued by shantytowns, open sewers, and recurrent cholera epidemics. A strategic side-effect of widening the streets was the reduced ability to build barricades, as had been done during the uprisings of 1830 and 1848.

Paris remained a vast construction site throughout the emperor’s twenty-year reign, making it difficult for the public to envision the final outcome. Only in later years did the monumental transformation become apparent, with wide boulevards finally showcasing the grandeur of the Arc de Triomphe (completed in 1836). Haussmann’s modernization supported an immense population increase of 180,000 during the first five years of Napoleon III’s rule.

His notoriety and extravagant spending made him a frequent target of gossip. The press eagerly reported allegations that Haussmann encouraged his daughter, Valentine, to become one of Napoleon III’s many mistresses, as well as rumors suggesting that a child from this affair had been passed off as the offspring of another woman. Despite the controversy, the emperor stood by him but never officially granted him the title of Baron, which Haussmann nonetheless used.

Persistent opposition from Baroche61, who strongly disfavored Haussmann, caused further delays in his projects. By early 1870, Haussmann lost key support, allowing his opponents—led by Prime Minister Émile Ollivier—to force his resignation. Had he remained in power for another two decades, one can only imagine how much further Paris might have evolved under his ambitious vision.