Bernard-Pierre Magnan (1791 – 1865), Marshal

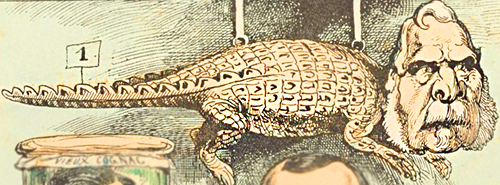

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: Lariviere (1853); 3rd: by Gerôme (1861); 4th: caricature by Giraud (24/3/1865).

Bernard Magnan’s journey to prominence stands in contrast to the elite of de Nieuwerkerke's16 salon. Born into humble beginnings, his father served as an attendant to the ill-fated Princess de Lamballe (unrelated to surgeon Jobert de Lamballe01), a court lady of Marie-Antoinette. After the Princess’s brutal murder by a revolutionary mob in September 1792, Magnan’s father turned to selling lemonade to support his family, which included the young Bernard.

Magnan entered the army and rapidly ascended through the ranks during campaigns in Spain and Portugal.

His marriage in 1824 to Sophie Roussel, the daughter of a division general, further bolstered his career; the union was officiated by King Charles X.

Magnan’s military achievements included a campaign in Algeria and service in Belgium beginning in 1830, where he attained the rank of brigade general.

A key figure in Louis-Napoleon’s coup d’état in December 1851, Magnan played a decisive role in suppressing the uprising with force. Subsequently, he acquired numerous titles and honors, including the cordon-rouge of the Legion d'Honneur Grand Croix title, awarded just one week after the coup.

Magnan notably attended a vendredi-soirée on January 9, 1852, where his presence was marked by the pride he took in wearing his red sash (cordon-rouge). Biard's36 depiction of him is rather absent-minded compared with Magnan’s fierce demeanor in other portrayals. According to the press, not all guests visited Biard’s atelier, and among those who did, some chose to pose only briefly. It is possible that Biard drew inspiration from Larivière’s painting of January 1853 for his composition. In 1870, caricaturist Paul Hadol aptly captured Magnan’s fierce reputation, portraying him as Napoleon III’s ferocious crocodile.

Magnan was not always domineering; he enjoyed attending balls and musical events. He even received a thank-you letter from composer Wagner, who expressed gratitude after Magnan praised his contemporary compositions and pledged support to secure the emperor's approval for additional concerts. Inspired by Magnan's compliments, Wagner incorporated a ballet section into his opera Tannhäuser specifically for his French audience.

A memorable anecdote recounts how Magnan, de Nieuwerkerke, and Lawoestine42 made an impression at a Tuileries ball in January 1853 by wearing shorts (culottes).

Financial instability shadowed Magnan’s life. Debts incurred by his passions —hunting, horse races, lavish visits to the baths in Dieppe, and hosting a weekly salon with Sophie for the aristocracy— led to the seizure of his furniture in Paris and Strasbourg. Viel-Castel43 calculated that, after Magnan's support for the coup, his annual income rose to 196,000 francs. He spoke warmly of Sophie's character after her sudden death in November 1858 from a minor illness. Bernard and Sophie had a son and five daughters.

A year later a marriage was announced between Magnan and the widow of Pair de France Jacques Paturle, who had inherited over eight million francs. Little is known about Sophie-Claudine (Lupin) Paturle (1793 – 1871) beyond her fortune. The marriage remains unconfirmed.

In 1862, Magnan was awarded the Masonic order of Grand Master by Emperor Napoleon III, despite never being affiliated with the lodge. Two months after caricaturist Giraud11 depicted him at a vendredi-soirée in March 1865, Magnan passed away at the age of seventy-three. General Mellinet, who was also present at that soirée, became his successor as Grand Master of the Masonic lodge.