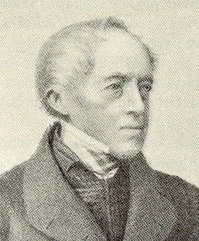

Count Gustaf Carl Fredrik Löwenhielm (1771 – 1856), diplomat

1st image: Biard; 2nd: Legion d'Honneur cross, without red sash; 3rd: Gravure by Hildebrand (1850s); 4th: by Sodermark (1815s). (Alternative: Heim)

Born in Sweden in 1771 to a noble family of French descent, Count Löwenhielm pursued his studies alongside his elder brother in Strasbourg, completing them in 1787.

Despite his slender frame, he embarked on a military career in cavalry and became a member of the royal guard of King Gustav III. During the 1792 assassination attempt on the king, Löwenhielm attempted to protect him, though unsuccessfully.

In the following years, he was entrusted with diplomatic missions to Russia, Berlin, and Vienna before being appointed ambassador to Paris in 1818 —a position he held, with only brief interruptions, for nearly four decades.

His tenure spanned two monarchies, multiple revolutions, a short-lived republic, and eventually the rise of an empire. He was honored as a Grand Officier in 1844 and received the Grand-Croix in 1855. Each of these titles would require him to visibly wear the red sash (cordon rouge) at official events. See, for example, the cordon rouge of count de Morny48. The absence of this insignia would favor the presence of painter Heim28b.

Known for his sharp intellect and lively spirit, Löwenhielm enjoyed participating in musical and social events. He was an accomplished clarinetist and often sang at gatherings.

Although no records confirm his presence at a vendredi-soirée, and Eugène Giraud11 did not create a caricature of him, de Nieuwerkerke16 frequently extended invitations to ambassadors.

Löwenhielm dined with Princess Mathilde on February 18, 1851 (a Tuesday), making it possible that he attended a vendredi-soirée on either February 14 or 21 that month. Horace de Viel-Castel43 once wrote of him:

"He is a good man, whose only fault is that he is too old."

By the early 1850s, Löwenhielm —then in his eighties— began experiencing cognitive decline. His reports and letters grew increasingly disorganized, though he remained unaware of the deterioration. Matters worsened following the death of his wife in 1853. His staff had occasionally stepped in to manage reports on Crimean War developments, yet his long-standing service record led the Swedish king to postpone his dismissal repeatedly.

Only in early 1856 did the king gently advise him in a letter to embrace retirement. Löwenhielm lamented this “greatest misfortune” but ultimately returned to Sweden, where he passed away several months later.