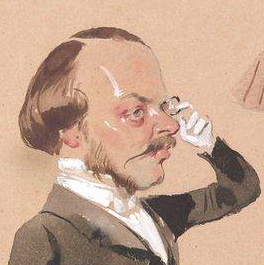

Emmanuel, viscount de Rougé (1811–1872), Egyptologist and Louvre conservator

1st image: Biard; 2nd: Glasses/lorgnette; 3rd: photo by Nadar(1860s); 4th: caricature by Giraud (March 28, 1851). (Alternative: Clement de Ris)

Emmanuel de Rougé’s noble lineage traced back to the 13th century, and his family’s wealth allowed him to pursue philology, specializing in Hebrew and Arabic. A pivotal moment in 1836 —an accidental encounter with a document on Egyptian grammar— redirected his focus toward deciphering hieroglyphs and Egyptian culture. His expertise earned him recognition in 1849, when he was appointed honorary conservator of the Egyptian section at the Louvre. That same year, he published the first edition of his overview of Egyptian artifacts housed in the museum.

mummy

Since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone by French soldiers in 1799 and its groundbreaking translation of hieroglyphs in 1822, Egypt had become a focal point for archaeologists like de Rougé and his assistant Mariette. By the late 1840s, French explorers had returned with hundreds of artifacts for exhibition at the Louvre

In 1851, de Rougé was invited to de Nieuwerkerke's16 vendredi-soirées, likely due to the influence of his advocate, de Saulcy69, who had extensively traveled across North Africa in the 1840s. That year, de Rougé presented his findings on hieroglyphics, inspiring Giraud11 to create a vivid caricature depicting de Rougé alongside a mummy.

A 1854 Ménestrel article confirmed his presence in Soirée au Louvre, stating:

“Fortoul has a discourse with archaeologists.”

However, after the revision of the painting, Fortoul46 is no longer engaged in conversation —and de Rougé is seated far away from him. The same is true for the other archaeologist, Longpérier37.

In February 1853, de Rougé was awarded the Chevalier rank in the Légion d’Honneur alongside fellow conservator de Reiset65.

Collaborating with distinguished German archaeologist Karl Lepsius, de Rougé developed a systematic approach for analyzing hieroglyphic discoveries. He also proposed the theory that the Phoenician alphabet had originated from Egyptian hieroglyphics, though later research suggested its roots lay in groups of Semitic laborers in Egypt.

De Rougé became a professor of Egyptology at the Collège de France, a senator, and a prolific author —publishing numerous books and articles while continuing his explorations in Egypt between 1863 and early 1864.

The only blemish on his distinguished career was his tumultuous marriage to Valentine-Marie de Ganay, whose affairs nearly bankrupted him. They eventually separated, and she entered a convent in Rue des Postes (now Rue Lhomond).