Louis-Félicien-Joseph Caignart de Saulcy (1807 – 1880), numismate, conservator, amateur archeologist

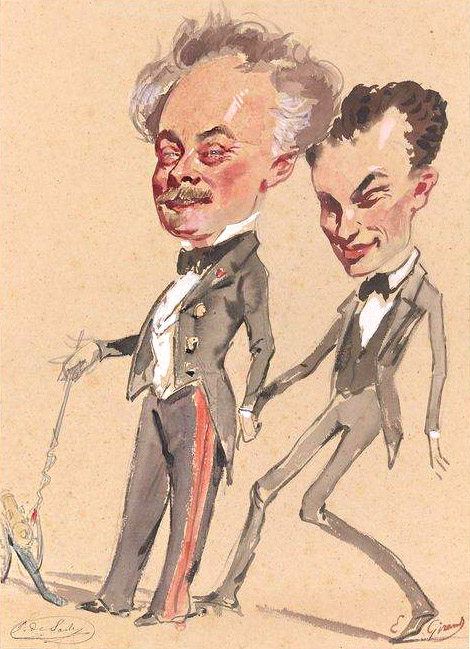

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: by Giraud (1852); 3rd: by Heim (1856); 4th: by Schultz (1865).

Félix de Saulcy, both conservator and archaeologist, studied at the École Polytechnique and served as conservator of the Artillery Museum in Paris from 1841 until Penguilly d’Haridon57 succeeded him in 1856. He was invited to de Nieuwerkerke's16 soirée on Friday January 15, 1852, to present his sensational discoveries from his journey to the Holy Land.

Eugène Giraud11 humorously depicted him hand in hand with his son, firing a cannon —a nod to his artillery background and the explosive debates that were sparked by his findings.

In December 1850, following the sudden death of his wife, Pauline de Brye (daughter of a numismatist), Félix and his son, eighteen-year-old Félicien, had embarked on an exploration trip to the Levant: Syria and Palestine. De Saulcy was deeply passionate about archeology, entomology, mollusks, and numismatics (ancient coins). He had researched Byzantine and Crusade coins in earlier years and deciphered a Phoenician text found near Marseille in 1847.

His amateur findings regularly offered creative reasoning that raised eyebrows among scholars, who primarily researched from their armchairs. Between December 1850 and April 1851, Félix and Félicien explored the Holy Land, recently accessible for relatively safe travel. During the journey, he excitedly reported to the Institute his discovery of the tombs of the kings of Judah. These claims created a sensation.

Upon his return, he brought a sarcophagus lid he attributed to King David. In press articles (e.g., l’Illustration, March 1852) and his 1853 book Narrative of a journey round the Dead Sea, he described discovering the ruins of Sodom and Gomorrah and his excavations at the Tombs of Kings.

However, skepticism grew as experts, including renowned historian and linguist Renan27a, criticized his findings, dismissed his drawings as fakes, and applied the adage, “He who comes from far away can lie well.”

Undeterred, de Saulcy sought to defend his claims with military determination. In 1853, he sent painter Auguste Salzmann to document the sites using photography —a modern medium Salzmann opposed.

The resulting 174 images confirmed the existence of ruins but did not substantiate de Saulcy’s conclusions. The tombs north of Jerusalem, which de Saulcy attributed to King David, were later identified as belonging to the royal family of Adiabene.

Aided by his Egyptologist brother Ernest and with help from his friends: travelers and experts Mérimée54 and Viollet-le-Duc40a, de Saulcy fiercely debated his findings with his academic rivals.

In December 1852, de Saulcy married Mathilde Billing, the 19-year-old daughter of a baron and diplomat Adolph Billing, who had died the previous month. De Saulcy joined Prince Napoleon on a North Pole expedition in 1856 and became a senator in 1859. His wife was appointed court lady to the Empress.

He returned to the Middle East in 1863, keen to prove his critics wrong. In December, his crew unearthed an unknown tomb in Jerusalem. The contents —a queen’s body wrapped in gold cloth— immediately disintegrated upon exposure. The Jewish community denounced the desecration, sparking a political battle.

De Saulcy had the sarcophagus smuggled out of the country to the Louvre, and the finding site, referred to as the “Tombs of the Kings” was purchased by the Jewish banking family Pereire, and later donated to the French government. Even today it remains under French ownership.

Although confirmed by Renan and other experts that the sarcophahagus wasn't of a queen of Judah, and the tomb wasn't one of Kings, but belonged to Helen of Adiabene, the Louvre labeled the sarcophagus as originating from the kings of Judah. Even today, this “Tombs of the Kings” area is subject to controversy between France, Palestine, and Israel.

A renowned numismatist, de Saulcy amassed an extensive collection of coins and artifacts. Declining a 500,000-franc offer from a London museum, he sold the collection to the Louvre for 300,000 francs to keep it in France. His health deteriorated over several years, and he passed away in Paris at the age of seventy-three.